Self-care

As youth workers, we often find ourselves in the role of the listener, the motivator, the safe space, and sometimes even the emotional anchor. We show up for young people in moments of crisis, confusion, and growth—but one of the most powerful things we can do is help them learn how to show up for themselves. And that’s where self-care comes in—not just as something nice to have, but as a core skill in mental health management.

Helping young people understand self-care means showing them that it’s not only okay to take care of their mental and emotional health—it’s necessary. It’s helping them recognize that tuning into their needs, setting boundaries, asking for help, and doing things that recharge them isn’t indulgent—it’s strength. Whether it’s guiding them to breathe through stress, reflect through journaling, find joy in a creative outlet, or simply get enough rest, we’re equipping them with tools that build resilience.

But here’s the thing—we can’t offer what we don’t model ourselves. If we don’t believe in self-care, or constantly run on empty, young people pick up on that too. They learn not just from our words, but from how we treat ourselves. So part of our job—part of our responsibility—is to also pause, breathe, and recharge. Not just for our own wellbeing, but to be better at holding space for theirs.

In the end, teaching self-care isn’t just about sharing coping tools. It’s about building a culture of care—where young people feel empowered to protect their mental health, and where they know they’re not alone in figuring it all out. In this part, we will try to help you build an image of what management practices can be used by youth, why they sometimes fail and how to help them go back on track.

Coping mechanisms

Coping mechanisms are the psychological and behavioral strategies individuals use to manage emotional distress and adversity. The effectiveness of these mechanisms depends on their ability to foster resilience and promote long-term well-being.

Adaptive coping mechanisms include engaging in creative expression (writing, painting, music), seeking social support, practicing mindfulness, developing self-awareness, and cultivating meaning through rituals, spirituality, or community engagement. These approaches help individuals navigate emotional pain without suppressing it, allowing for the integration of difficult experiences into a broader narrative of growth and self-understanding.

Maladaptive coping mechanisms, on the other hand, involve avoidance, emotional suppression, self-harm, substance abuse, compulsive behaviors, or excessive rumination. While these may provide temporary relief, they often exacerbate distress in the long run by preventing true emotional processing and healing.

The ability to adopt adaptive coping strategies is influenced by personal history, social environment, and access to support systems. Encouraging reflective self-exploration and fostering spaces for meaningful emotional engagement can empower individuals to develop healthier ways of coping with psychological distress.

Types of coping mechanisms

Not all coping strategies are good for us. Some help us grow and bounce back stronger—others might feel helpful in the moment, but can actually cause more harm over time. As youth workers, it’s important that we not only support young people through their tough moments but also help them recognize how they’re coping—and whether it’s really serving them.

Let’s talk about coping mechanisms in a way that makes sense. Coping usually shows up when something stressful happens—like an argument with a friend, failing a test, feeling left out, or going through a big life change. These stressful moments (we call them stressors) push people to react. And that’s when different coping styles kick in.

Now, coping can go two main ways:

1. Problem-focused coping

This is when someone tries to do something about the issue.

Fix it. Change it. Solve it.

For example: A young person realizes they’re falling behind in school. They talk to their teacher, create a study plan, and ask for tutoring help. They’re tackling the issue head-on.

2. Emotion-focused coping

This is about handling the feelings that come with the situation—especially when you can’t fix it directly.

For example: After a breakup, a teen might journal their thoughts, cry it out, call a friend, or do something creative to release emotion. The pain is real, and they’re making space to feel it instead of ignoring it.

Let’s put this into a story:

If they use problem-focused coping, they might call the bank, freeze the card, and check their budget to stay afloat until it’s resolved.

If they use emotion-focused coping, they might order comfort food, talk it out with someone they trust, or distract themselves with a favorite movie.

If they use a blend of both, maybe they start by calling a friend who went through something similar. They get advice, reassurance, and a clear plan. That gives them the emotional strength to handle the practical steps—and they still allow themselves some comfort along the way.

This is what we call active coping—doing something, either about the stressor or about how it feels. And that’s what we want to encourage: coping that helps young people adapt, stay grounded, and keep moving forward.

But we also need to watch out for maladaptive coping—the kind that numbs, avoids, or harms. Things like withdrawing from everyone, using substances, or blaming themselves might feel like relief in the short term, but they don’t support long-term mental health. That’s where our guidance really matters.

By helping young people explore different coping tools—and showing them that it’s okay to ask for help, to feel what they feel, and to take positive action—we’re giving them lifelong skills.

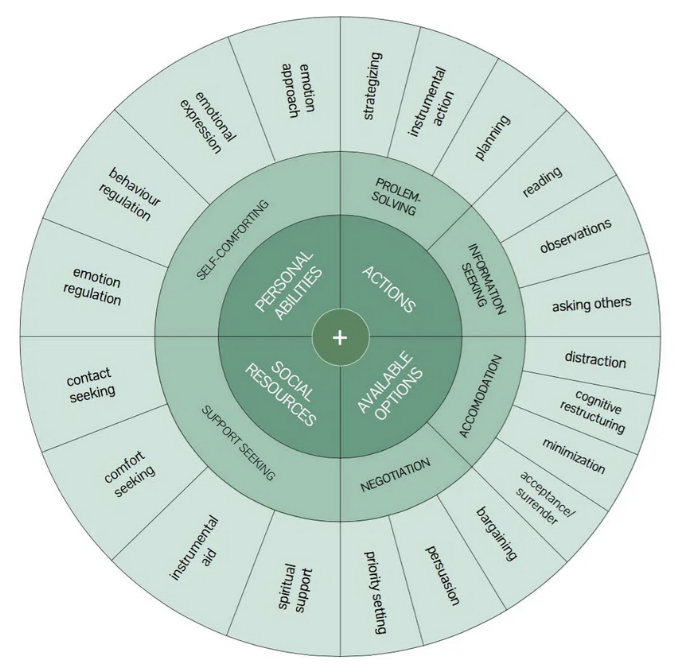

To help you understand this further, here is the wheel of coping:

It is important to be aware that these coping strategies can be used by anyone, but they can’t always help. What does this mean? Coping mechanisms are useful mainly with the youth encountering distress of light mental health problems – in these situations, self-help is a skill that can bring them to the positive state of mental health. However, sometimes self-help and coping mechanisms as such are not enough.

In case of youth experiencing more severe mental health problems and mental disorders, professional help is often needed. In situations when youth are in crisis, these mechanisms are most likely not to be effective. However, there are moments when these young people are in remission (do not expose symptoms) and have good periods – it is recommendable for young people to use a combination of self-help and professional help, as these can keep them on track and provide a positive result. Our recommendation is however, to encourage youth with more severe conditions to discuss self-help mechanisms with professionals they are seeing, in order for them to be maximally effective.

Adaptive coping mechanisms include engaging in creative expression (writing, painting, music), seeking social support, practicing mindfulness, developing self-awareness, and cultivating meaning through rituals, spirituality, or community engagement. These approaches help individuals navigate emotional pain without suppressing it, allowing for the integration of difficult experiences into a broader narrative of growth and self-understanding.

Maladaptive coping mechanisms, on the other hand, involve avoidance, emotional suppression, self-harm, substance abuse, compulsive behaviors, or excessive rumination. While these may provide temporary relief, they often exacerbate distress in the long run by preventing true emotional processing and healing.

The ability to adopt adaptive coping strategies is influenced by personal history, social environment, and access to support systems. Encouraging reflective self-exploration and fostering spaces for meaningful emotional engagement can empower individuals to develop healthier ways of coping with psychological distress.

Coping mechanisms are the psychological and behavioral strategies individuals use to manage emotional distress and adversity. The effectiveness of these mechanisms depends on their ability to foster resilience and promote long-term well-being.

Adaptive coping mechanisms include engaging in creative expression (writing, painting, music), seeking social support, practicing mindfulness, developing self-awareness, and cultivating meaning through rituals, spirituality, or community engagement. These approaches help individuals navigate emotional pain without suppressing it, allowing for the integration of difficult experiences into a broader narrative of growth and self-understanding.

Maladaptive coping mechanisms, on the other hand, involve avoidance, emotional suppression, self-harm, substance abuse, compulsive behaviors, or excessive rumination. While these may provide temporary relief, they often exacerbate distress in the long run by preventing true emotional processing and healing.

The ability to adopt adaptive coping strategies is influenced by personal history, social environment, and access to support systems. Encouraging reflective self-exploration and fostering spaces for meaningful emotional engagement can empower individuals to develop healthier ways of coping with psychological distress.

Why coping mechanisms matter for mental well-being

When a young person is dealing with mental distress or a light mental problem, above mentioned coping mechanisms can be very useful for maintaining their well-being. Healthy coping responses can guide you from a state of stress or agitation back into a sense of balance. They often activate your inner problem-solving mode, allowing you to zero in on aspects of a situation that are within your influence, such as your behavior or emotional reactions.

The point of such mechanisms is focusing on what we can control. That means that even though the core reason or trigger of mental distress and mental health problems can be something external, we need to focus on everything we can do from the inside for the sake of our well-being. That leads us to the psychological term internal locus control – your belief in your capacity to to influence outcomes in your life. People with strong internal locus control are more likely healthier, more satisfied with life and more resilient. On the other hand, people with external locus control tend to often look to outside forces to steer their actions or choices. This mindset often leads to passivity, discouragement, dissatisfaction and reliance on less effective ways of coping. Even though there are things and situations that are out of our hands, we still need to focus on small changes within ourselves to increase resilience, acceptance and flexibility.

Take a quick look on the differences between a person with internal locus control and a person with external locus control:

By switching our focus on what we can control — even if that’s just how we change our emotional reaction to a situation — can significantly improve our overall well-being. When we manage our reactions, our outlook often shifts, even if the circumstances stay the same. This emotional shift can reduce the chances of experiencing issues like anxiety, depression, low self-worth, or turning to harmful coping patterns.

When we take initiative and manage what’s within our control, we’re more likely to feel empowered, because we give the situation a new frame, we look at it from another perspective and we are actually able to realise that there is a solution. We realise that there is not much we can change in that external situation, but that internal changes are the ones that really matter.

Recognize unhealthy coping patterns

There are situations in which a young person can say how they are dealing with a problem perfectly fine and how it is helping them. Be careful! Always try to check how they are dealing with the problem and what the actual problem is. Young people can engage in activities that result in them feeling better, which is most of the time only a short-term “help”. To be able to engage in healthy coping mechanisms a person must be completely aware of what is the problem, why the problem exists and that coping mechanisms take time to notice they feel better, they are effective in the long-term. These are some of the signs that a young person is engaged in unhealthy coping patterns:

- Increasing reliance on substances such as alcohol, recreational drugs, or medications.

- Emotional eating or consuming excessive processed, sugary, or high-fat foods.

- Ignoring or denying that a problem exists.

- Using distractions like excessive partying, gaming, or thrill-seeking to escape reality.

- Impulsive or excessive spending.

- Minimizing or dismissing the seriousness of the issue.

- Sudden and dramatic changes in routines—such as eating, sleeping, or exercise habits.

- Constantly venting without taking steps to improve the situation, or seeking help but rejecting it.

- Social withdrawal and disconnection from people, activities, or interests once enjoyed.

Be patient with young people, explain that everything is a process and that by implementing healthy coping patterns they will notice change, but not immediately. Maintaining well-being is not an overnight thing, it requires patience and consistency, it is hard and challenging, but definitely worth it.

Healthy coping strategies for tough emotions

Tough emotions are situations where anxiety, depression, stress hit hard, so that they make staying focused and taking the right decisions challenging. Below is the list of self-coping mechanisms you can encourage young people to use, depending on their problem.

Let’s talk about coping mechanisms in a way that makes sense. Coping usually shows up when something stressful happens—like an argument with a friend, failing a test, feeling left out, or going through a big life change. These stressful moments (we call them stressors) push people to react. And that’s when different coping styles kick in.

Coping mechanisms for anxiety

Keep a journal

When anxiety takes over, try to sit down and write exactly what you feel and why. Writing will allow you to calm down your racing thoughts, reduce mental clutter, reflect, problem-solve or simply vent in a safe space. Facing your fears through writing might seem intimidating, but it allows you to explore worst-case scenarios and realize that you could manage them if they occurred — giving you a sense of preparedness and control. By implementing journaling for a longer period of time, you will get written proof that you got better at managing your anxiety, fears and weaknesses!

Prioritize your physical needs

Since anxiety has physical symptoms, it is important to take care of your body as well. Quality sleep can impact your emotional regulation, cognitive function and physical health while lowering stress hormones and enhancing resilience to anxiety. Proper hygiene can help reduce anxiety by promoting a sense of control, boosting self-esteem and providing physical comfort, which fosters a calmer, more positive mindset. Balanced nutrition can help manage anxiety by stabilizing blood sugar levels, supporting brain function, and regulating mood-enhancing chemicals in the body.

Move your body

Being physically active can help when dealing with anxiety because it releases feel-good hormones like endorphins and dopamine. Whether it’s a walk, dance session, or workout class, physical activity boosts mood and improves sleep — both important when managing anxiety.

Coping strategies for managing stress

Deep breathing

Deep breathing can be helpful in managing stress by activating the body’s parasympathetic nervous system, which promotes relaxation and reduces the physiological symptoms of stress, such as increased heart rate and shallow breathing. To do it, inhale deeply through your nose for 4 seconds, hold for 4 seconds and then slowly exhale through your mouth counting to 6 or 8. This simple practice allows you to refocus, calm your mind and reduce the intensity of stress responses.

Release muscle tension

Releasing muscle tension helps manage stress by relaxing the body and reducing physical discomfort. Try to progressively tense each muscle group, starting from your toes and going upwards, hold the tension for a few seconds and then release it. This technique can be done anytime you feel stressed, especially when you notice physical symptoms of stress. It helps by breaking the cycle of stress-induced muscle tension, promoting relaxation and mental clarity.

Practice mindfulness

Practicing mindfulness doesn’t only mean mediation, you can simply pay attention to your surroundings, breathing or the sensation in your body during different activities during the day, without judgment – just observe. Mindfulness is beneficial anytime you’re feeling stressed, as it helps you stay grounded and increase your ability to respond calmly to stressors.

Coping mechanisms for depression

Break tasks down and prioritise

By making overwhelming tasks feel more manageable, reducing feelings of helplessness and providing a sense of accomplishment by achieving each small task, dealing with depression will become easier overtime. By focusing on smaller, achievable steps and tackling them in order of importance, it prevents procrastination and boosts motivation.

Use affirmations

Releasing muscle tension helps manage stress by relaxing the body and reducing physical discomfort. Try to progressively tense each muscle group, starting from your toes and going upwards, hold the tension for a few seconds and then release it. This technique can be done anytime you feel stressed, especially when you notice physical symptoms of stress. It helps by breaking the cycle of stress-induced muscle tension, promoting relaxation and mental clarity.

Reach out to others

Asking for help, advice and support might feel vulnerable, but it is a powerful and necessary step for healing. Start by opening up to your family members, friends, peers or colleagues. There is somebody who will understand you, take you seriously and support you during the healing process. There is always a person with whom you will feel safe enough to be vulnerable.

Psychological defense mechanisms

Psychological defense mechanisms

Have you ever felt something so deeply—fear, sadness, anger—but didn’t quite know how to deal with it? Maybe you laughed during a sad moment, snapped at a friend for no reason, or avoided thinking about something upsetting. Don’t worry—your brain was likely just trying to protect you.

These automatic reactions are called psychological defense mechanisms. Think of them as your mind’s way of defending you from emotional overload. They’re like invisible armor that steps in when things feel too tough to handle. The cool (and sometimes tricky) part is that we often don’t even realize we’re using them.

Defense mechanisms are natural and unconscious ways we protect ourselves from emotional pain or anxiety. They can be helpful, but they can also backfire if used too often or in the wrong situations. Psychologist George Vaillant actually grouped them into four levels based on how helpful (or harmful) they are in the long run.

Let’s go through these four levels—from the least helpful to the most healthy—and meet some of these “mind shields” through real-life examples.

| Defense Mechanism | Brief Description | Example |

| Displacement | Taking feelings out on others | Being angry at your boss but taking it out on your spouse instead |

| Denial | Denying that something exists | Being the victim of a violent crime, yet denying that the incident occurred |

| Repression | Unconsciously keeping unpleasant information from your conscious mind | Being abused as a child but not remembering the abuse |

| Suppression | Consciously keeping unpleasant information from your conscious mind | Being abused as a child but choosing to push it out of your mind |

| Sublimation | Converting unacceptable impulses into more acceptable outlets | Being upset with your spouse but going for a walk instead of fighting |

| Projection | Assigning your own unacceptable feelings or qualities to others | Feeling attracted to someone other than your spouse, then fearing that your spouse is cheating on you |

| Intellectualization | Thinking about stressful things in a clinical way | Losing a close family member and staying busy with making the necessary arrangements instead of feeling sad |

| Rationalization | Justifying an unacceptable feeling or behavior with logic | Being denied a loan for your dream house, then saying it’s a good thing because the house was too big anyway |

| Regression | Reverting to earlier behaviors | Hugging a teddy bear when you’re stressed, like you did when you were a child |

| Reaction Formation | Replacing an unwanted impulse with its opposite | Being sad about a recent breakup, but acting happy about it |

Psychiatrist George Eman Vaillant introduced a four-level classification of defence mechanisms. In monitoring a group of men from their freshman year at Harvard until their deaths, the purpose of the study was to see longitudinally what psychological mechanisms proved to have impact over the course of a lifetime. The hierarchy was seen to correlate well with the capacity to adapt to life. His most comprehensive summary of the on-going study was published in 1977. The focus of the study is to define mental health rather than disorder.

- Level I – pathological defences (psychotic denial, delusional projection)

- Level II – immature defences (fantasy, projection, passive aggression, acting out)

- Level III – neurotic defences (intellectualization, reaction formation, dissociation, displacement, repression)

- Level IV – mature defences (humour, sublimation, suppression, altruism, anticipation)

LEVEL 1: PATHOLOGICAL DEFENSES

Rare but serious—distorting reality to the point of disconnection.

In youth work, these may appear in young people who've experienced trauma, long-term neglect, or are dealing with deeper psychological challenges. They might not seem grounded in reality—and it's important to approach these moments with care, and possibly in coordination with mental health professionals.

What you might see?

Youth work approach:

LEVEL 2: IMMATURE DEFENSES

Common in teens—protective, but often harm relationships

These defenses are very familiar in youth settings. They show up during conflict, feedback, stress, or emotional overwhelm. They often signal a young person feeling vulnerable and lacking the tools to cope.

What you might see?

Youth work approach:

"It feels like something's bothering you. Want to talk about it later?"

LEVEL 3: NEUROTIC DEFENSES

Protective but avoidant—functional in the short-term, limiting in the long-term

These defenses are more subtle. Youth using them may appear "fine" on the surface but are actually avoiding real emotion or inner processing.

What you might see?

Youth work approach:

"You've shared a lot about what happened—but how did you feel in that moment?"

LEVEL 4: MATURE DEFENSES

Healthy coping—these are the tools we want to encourage and strengthen

These defenses show emotional growth. Youth using them are starting to feel their feelings and use them constructively. This doesn't mean they never struggle—but they're learning to ride the waves instead of avoiding them.

What you might see?

Youth work approach:

"It's really powerful how you're expressing this through your art."

"What's changed for you? What helps you face things better now?"

Which coping style works the best? Help your young people find out

One of the most empowering things we can do is help them build a personal coping framework—a kind of internal toolbox they can turn to when things feel overwhelming. Here’s how we can walk alongside them in that process:

1 - Recognize the emotion — for example, “frustration”

The brain region responsible for intense emotional reactions is different from the one that handles logic and problem-solving. In order to cope effectively, these parts need to work together. One way to bridge them is by naming the emotion. Labeling what young people are feeling can activate the thinking brain and help them make sense of what’s going on.

Keep in mind that simply identifying a feeling won’t always make it disappear. That’s okay. When labeling isn’t enough, you can suggest them to turn to tools that help them process — like drawing, writing in a journal, or taking a walk. Over time, they’ll learn which strategies help them regulate and which ones don’t. Support them in discovering which strategies work best, and encourage them to notice and keep track of what helps them feel more regulated.

2 - Help youth decide on a coping strategy

Once the emotion is named, help the young person take a step back and assess:

“How much influence do you have over this situation?”

This question is powerful because it points them toward the most appropriate coping approach.

If they do have some control, support them in using problem-focused coping:

- Help them break down what they can do

- Encourage them to create a to-do list or action plan

- Offer to roleplay conversations or situations

- Help them identify someone they trust to talk to

If the situation feels out of their hands, or they’re just too overwhelmed to act right away, guide them toward emotion-focused coping. Encourage them to do something that supports their emotional state:

- Listen to music

- Practice yoga or deep breathing

- Watch something uplifting

- Take a moment to rest or self-soothe

Let them know that both styles are valid—what matters most is choosing what helps in that specific moment.

3 - Focus on what is within their control

Even when a situation feels completely out of their control, young people still have power over how they respond. You can help them tap into that by asking:

“What would your ideal outcome look like?”

“What’s one small step that could move you closer to that?”

These types of questions promote a solution-focused mindset, and often reveal actions they hadn’t considered yet.

In situations where change isn’t possible—like dealing with grief or disappointment—acknowledge that with care. You might say:

“You’re right, you can’t change this part. But you can decide how to take care of yourself right now.”

Whatever the challenge, remind them to show themselves compassion. Ignoring or minimizing emotions may feel easier in the short term, but can build up over time. Instead, support them in feeling what they feel—and moving forward with greater self-awareness and emotional strength.

Coping Habits

Start by encouraging young people to notice what's causing their stress. Stress can feel overwhelming when it's vague or bottled up. By helping them name specific stressors—whether it's school pressure, a friendship issue, or something at home—they can begin to understand what they're dealing with.

Try using questions like:

- "What's been weighing on you lately?"

- "When do you usually start feeling stressed during the day?"

The clearer the source, the easier it becomes to choose a helpful coping response.

Invite them to reflect on how they currently respond to stress. Are they withdrawing? Shutting down? Scrolling endlessly on social media? Getting angry?

Together, look at which responses are actually helping, and which ones might be causing more harm.

It can be helpful to say something like:

"Let's figure out which of your go-to habits are helping you feel better, and which ones might be adding more stress in the long run."

No judgment—just honest reflection.

Let them know it's okay if the first coping tool they try doesn't work perfectly. Part of learning to cope is experimenting.

Suggest a few different tools they can test out:

- Breathing exercises or meditation apps

- Listening to a calming playlist

- Doodling or journaling

- Going for a short walk

- Talking to someone they trust

Let them know it's about finding what clicks for them—not what works for everyone else.

Coping shouldn't only happen when there's a crisis. Help young people build mini routines that support them day-to-day.

This could be:

- Taking 5 quiet minutes before class

- A daily music break

- Ending the day by journaling a few thoughts

- Regular check-ins during youth group sessions

By making these small practices part of their normal routine, they'll be more prepared when bigger stressors show up.

Sometimes, young people need more support than we can offer alone—and that's okay.

Let them know that talking to a mental health professional isn't a sign of weakness—it's a sign of strength.

You might say: "There are times when everyone needs a little extra support, and there are people trained to help with that. Would you like me to help you find someone to talk to?"

Be ready to connect them with local counselors, school psychologists, or helplines if needed.

Understanding Coping vs Defense Mechanisms

It's helpful to explain the difference between coping and defense mechanisms in ways they can relate to.

Coping strategies are things we choose to do to help us feel better or solve a problem.

Defense mechanisms happen more automatically—like ignoring a problem or pretending it doesn't matter. These often kick in when something feels too overwhelming.

You can gently explain:

"Sometimes our brain tries to protect us by pushing things away or pretending we're fine. That's normal. But when we avoid dealing with stuff, it usually builds up. That's why learning healthy coping tools matters—they help us actually feel better and move forward."